Environmental sensing networks play a vital role in understanding the state of the environment and driving effective action on climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem health. These networks consist of spatially distributed sensors that continuously collect data on physical, chemical, and biological variables, enabling researchers, policymakers, and communities to observe changes over time and make data-driven decisions. However, one of the often underestimated challenges for long-term, large-scale environmental monitoring systems is the selection and integration of materials that can withstand environmental stressors while preserving data integrity. This includes everything from mechanical stability under shifting weather conditions to resilience against thermal fluctuations, moisture, corrosion, and biological fouling.

Deployments in challenging environments—arctic tundra, coastal zones, forests, deserts, and even industrial hotspots—can expose sensors and associated components to extremes of temperature, humidity, and physical impact. Ensuring consistent performance across these conditions requires thoughtful material choices that balance durability, sensitivity, and ecological compatibility. In long-duration networks, the quality of data is only as good as the hardware’s ability to endure its operating environment without drift or unexpected failure. In this context, materials such as thermally stable quartz tubing for high-reliability environmental sensor networks are increasingly considered for protective pathways and sensor housings because of their resistance to temperature-induced deformation and chemical neutrality.

As sensor networks scale both in size and deployment duration, understanding the interplay between environmental demands and materials performance becomes essential. Designers of sensing systems must think beyond simple connectivity or data transmission protocols and address material-linked phenomena that can introduce systematic bias or sensor degradation over time, such as expansion and contraction due to thermal cycling or corrosion from saltwater exposure. Addressing these challenges not only increases the operational lifespan of sensors but also enhances the sustainability and competitiveness of environmental monitoring initiatives worldwide.

Why Material Robustness Matters in Environmental Sensors

Environmental sensors capture accurate measurements of variables such as temperature, humidity, air quality, soil moisture, barometric pressure, water quality, and pollutant concentrations. Conventionally, designers have emphasised software accuracy, data storage, and communication bandwidth, while treating material selection as a secondary consideration. Emerging research shows that material properties significantly influence sensing system performance, especially in applications that require long-term reliability.

For example, materials that undergo physical changes under extreme conditions can alter the calibration of a sensor, introduce noise in signal processing, or even cause outright structural failure that leads to data loss. Materials that resist expansion and contraction across wide temperature ranges—such as high-purity glasses and ceramics—help maintain geometric stability, preserving optical, mechanical, and thermal pathways within sensing devices. Similarly, chemical resistance against pollutants and salt spray extends the functional life of sensors in coastal or industrial areas.

Materials engineering plays a crucial role in environmental sensing by helping reduce lifecycle costs and minimize environmental footprints. Robust materials reduce the need for frequent replacements, recalibrations, and maintenance visits, thereby lowering the overall energy and resource costs associated with monitoring infrastructure. As sustainability principles become increasingly linked to environmental sensing practices, choosing materials that align with these goals also contributes to minimizing waste and promoting responsible design.

Material Challenges in Diverse Monitoring Environments

Environmental scientists deploy sensing networks across a wide range of ecological and climatic settings, and each setting presents its own material challenges.

Arctic and Alpine Zones

In regions subject to extreme cold, many polymer-based components become brittle and lose elasticity, leading to cracks and eventual failure. Additionally, humidity changes between freeze and thaw cycles can penetrate housings, causing condensation and electronic short circuits. Materials used in these environments must resist embrittlement and maintain structural integrity across wide temperature ranges.

Coastal and Marine Settings

Marine environments present a unique set of material hazards: high salinity, wind-driven abrasion, prolonged UV exposure, and biological fouling from algae and organisms. Saltwater corrosion is particularly aggressive on many metals and traditional coatings, demanding alternatives such as special alloys, ceramics, and glass that resist chemical attack.

Tropical and Rainforest Climates

High humidity and heavy rainfall accelerate corrosion, facilitate mold growth, and can degrade adhesives and sealants over time. Sensing equipment in these environments must be designed with moisture-blocking materials and robust sealing systems to prevent water ingress and maintain accurate readings.

Urban and Industrial Areas

Urban monitoring stations often contend with contaminants such as dust, soot, corrosive gases, and vibration from nearby machinery. These factors can degrade sensor components, introduce drift, and mask true environmental signals if not accounted for in the material selection phase.

Each of these environments underscores the need for robust materials that can not only survive but continue to deliver accurate data over years of operation. Structural materials, coatings, insulation, and sensor interfaces all play a role in ensuring the long-term viability of these networks.

Innovations in Materials for Environmental Sensing

Advances in materials science are driving improvements in sensor performance and durability. High-tech ceramics, engineered glasses, advanced polymers, and composite materials are increasingly used to address specific environmental challenges. “Smart” materials that offer self-healing capabilities, microstructured surfaces to resist biofouling, and nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical properties are reaching maturity for commercial deployment.

Glass and quartz materials, in particular, offer a combination of thermal stability, chemical inertness, and optical clarity that is valuable in many sensing applications. These materials can serve as protective tubing, housings, calibration references, and optical windows in instruments where physical and optical stability influences data quality. Similarly, coated ceramics or glass composites are used in protective housings that resist corrosive environments while maintaining thermal equilibrium.

In addition to material performance, manufacturability and lifecycle considerations are playing a larger role in sensor design. Sustainable materials that are recyclable, non-toxic, and compatible with lifecycle reuse frameworks align with global initiatives emphasizing responsible resource use and reduced environmental impact.

Calibration and Measurement Precision

Measurement precision lies at the heart of environmental sensing. Poor calibration can introduce systematic errors that undermine the validity of datasets used for policy, management, and scientific research. Calibration strategies often rely on reference standards and stable material surfaces against which instruments are compared during maintenance or pre-deployment checks.

Components such as optically flat quartz plates for calibration of precision environmental instrumentation provide consistent, low-expansion surfaces that assist in maintaining measurement accuracy over the long term. These materials are selected for their ability to preserve flatness and reflectance properties even under repeated thermal cycling, ensuring that calibration references do not drift over time. High-precision calibration surfaces are essential for instruments measuring spectral characteristics of light, atmospheric particulates, and optical turbidity in water monitoring systems.

Sensor Networks and Sustainable Design

In recent years, the concept of “sustainable sensor networks” has emerged, emphasizing not just the data value but the environmental footprint of the sensing infrastructure itself. Sustainable sensor networks aim to minimize materials waste, reduce energy consumption during operation, and consider end-of-life recycling or disassembly to lessen ecological impact. :contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

Durable materials play a direct role in achieving sustainable design goals by extending lifetimes and reducing the frequency of component replacement. Designing for longevity reduces the total materials output over the lifespan of a monitoring deployment, leading to lower resource extraction and waste generation. Additionally, choosing materials that are recyclable or easier to disassemble contributes to circular economy objectives in technology applications.

Design Considerations for Network Resilience

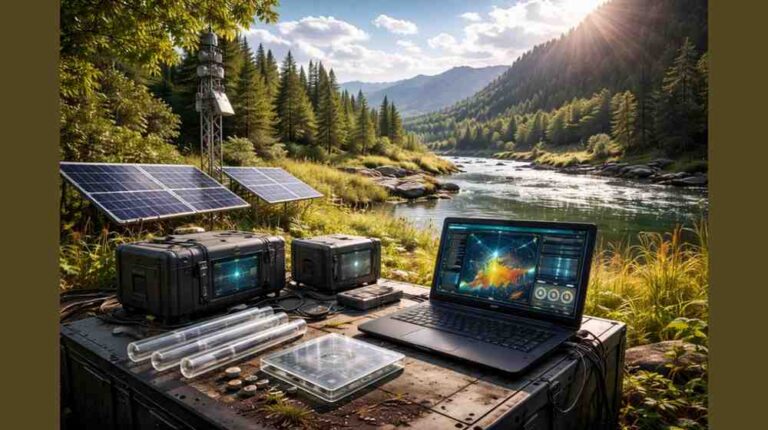

Beyond material selection, network designers must account for other resilience factors, such as energy management, communication reliability, and physical mounting strategies. Energy-neutral design principles that leverage solar harvesting, low-power protocols, and intelligent sleep cycles can enhance network operation in remote areas. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

Physical mounting strategies—such as elevated mounts to avoid flooding or corrosion-resistant anchor points—also contribute to resilience. Integrating materials and designs that complement these strategies improves not only sensor performance but also downstream data collection and analysis.

Implications for Policy and Environmental Decision-Making

Reliable environmental data is increasingly central to regulatory compliance, disaster response planning, and natural resource management. Policy frameworks around air quality standards, water quality monitoring, carbon emissions reporting, and habitat conservation all rely on accurate, verifiable data streams. Durable materials that support sensor reliability help ensure that decision-makers can trust the datasets generated by monitoring systems.

As environmental policy evolves to incorporate real-time data and near-zero latency reporting, sensor network design will increasingly intersect with governance, regulatory reporting, and public transparency. Ensuring that material-linked failure modes do not compromise data integrity is an implicit part of building public trust in environmental monitoring.

Conclusion

Next-generation environmental sensing networks are not simply about increasing sensor counts or transmitting more data; they are about building robust, resilient systems that deliver accurate and actionable information across years of challenging operation. Material science plays an indispensable role in this evolution, influencing everything from sensor housings and protective conduits to calibration surfaces and structural components.

By understanding the environmental demands on sensing networks and selecting materials with appropriate thermal stability, chemical resistance, and mechanical durability, designers can enhance the longevity and reliability of monitoring infrastructure. Durable materials not only reduce lifecycle costs and waste but also strengthen the foundations of evidence-based environmental decision-making in an era of rapid ecological change.